By Nancy Arsenault

Have you grown the tastiest tomato, the largest sunflower or the blue ribbon pumpkin at The Bolton Fair? You may have that same green thumb luck this season, IF you are a seed saver.

Seed saving, originally borne out of economical need, is gaining ground among growers hoping to reproduce their best specimens year after year. Others are saving seeds in order to avoid the mass produced hybridized seed varieties, believed by many to have been genetically modified by the big seed companies.

Those were some of the reasons given by a roomful of gardeners who filled Stow Town Hall a week ago to hear the Stow Garden Club presentation on the ins and outs of seed saving. Even though a colorful packet of seeds often costs just a few cents, these gardeners who nurture and coax their plants to maturity, if blessed with a spectacular specimen, feel ownership of that plant, and of its descendants.

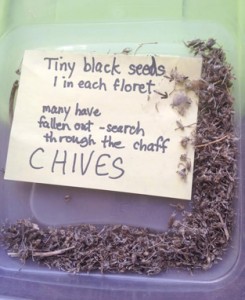

Stow’s MariePatrice Masse offered her presentation, “Confessions of a Seed Snatcher” accompanied by a massive seed giveaway that lined the walls of Town Hall – dried and labeled seeds in their original, harvested form, available for anyone who wanted to take a sample and try their luck. Masse is an enthusiastic gardener, cultivating a 4500sq ft plot at the Community Gardens on Tuttle Lane and it seems there isn’t a plant variety that Masse hasn’t met or hasn’t tried to proliferate through seed gathering.

With literally thousands of plants out there, how does a gardener know which are the best seeds to save? Masse said that the purest seeds will be produced by open pollenated, heirloom type plants, true to their original form. Self-pollinating varieties create seeds that will reproduce exactly in the form of the parents, giving the best chance to produce prime specimens from year to year. Hybridized seeds, many of those produced by commercial seed companies, are not as easy to save, nor do they give optimum results the following year.

Some of the easiest self-pollinators to save are beans, lettuce, peas, tomatoes and heirloom flowers likes cleome, foxgloves, hollyhock, nasturtium, sweet pea, and zinnia. Tomato seeds, when harvested at the optimal time, allowed to dry and then stored properly, can last up to four years before planting. Beans, peas and corn can last anywhere from two-three years.

“Proper storage is very important,” said Masse. “Store seeds in a cool, dry place, away from heat, light and moisture.” Masse displayed dozens of kitchen Tupperware containers, all holding individual seed varieties, and sealed air tight. “The biggest, healthiest plants produce the biggest, healthiest seeds,’” she said.

Harvest time is crucial to the viability of the saved seeds, over time, and differs with every single plant, based on their life cycle. For example, colorful Cosmos and Hollyhocks produce seed pods toward the end of their blooming season. Those pods should be left to dry on the stalk and then carefully opened to remove the seeds. Snapdragons and Balloon flowers produce seed pods that should also be left to dry, but their seeds are so numerous, and small, that it is best to cut the stalk, open the pods and shake their contents into a paper bag in order to catch them all.

And as for that giant pumpkin? Cut off the top as you would to carve a Jack-O-Lantern, have the kids sink their hands into the moist interior and pull out those seeds. Lay them out in a single layer to dry. If you are not going to roast and salt them for a snack, allow them to fully dry and store them for the next growing season. Some seeds can be stored in a freezer, in a basement, or in an attic, as long as attention to changing temperatures in those interior spaces is monitored, said Masse. She said the internet is a great resource regarding harvest times and techniques for a specific flower or vegetable variety.

If you become a seed saver, you also, by default, become a seed grower, and that means dedicating s portion of your home’s interior to the early and careful germination of these precious seeds. Masse fills dozens of small peat pots with tiny seeds, ultimately reaching for the sun in a southern exposure. Constantly checking the moisture levels so that the soil is not dried out is a big part of the job, said Masse. It helps if plants with similar germination times, light and moisture requirements are kept together, she added.

Courtesy Nancy Arsenault

As spring approaches, the delicate seedlings will need to be hardened off to the natural temperatures and outdoor conditions. Masse rotates her youngsters outside for about an hour each day for a week before they are ready to remain outside and in the ground. For those young plants that may have an aversion to the whole transplant process, Masse suggests a dose of aspirin, dissolved in a gallon of water, to help them through the transition. Even a shot of chamomile tea was reported to do the trick, according to one audience member.

After the presentation, the audience, many of whom had travelled from towns extending from the North Shore to the far side of central Massachusetts, filled ziplock bags with dried seeds collected by Masse. While it’s too late to rescue seeds from last year’s plants, Masse encourage the crowd to embrace the concept of seed saving this year, even beginning with just one tomato plant or favorite flower. Seeing the resulting success from producing and harvesting one’s own seeds from year to year, is truly a practice that supports sustainability in a changing and often uncontrollable world, she concluded.