By Ann Needle

Head to a major sporting event, and it is hard to imagine seeing one of the game’s stars standing outside the venue in full uniform. Former Boston Celtics starter Chris Herren did just that one evening—but, rather than being fan-friendly, Herren called himself “desperate,” waiting for his drug dealer to breeze by with his pre-game supply.

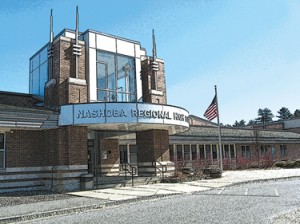

Herren shared his tale of the horror and desperation of substance abuse with the student body of Nashoba Regional High School last week, a story that ended his basketball career. After his recovery at age 34, five years later he continues to talk to student groups across the country about how the nightmare began, and where it took him before he walked away.

His appearance at the school was sponsored by the Tecumseh Foundation, a nonprofit established in honor of NRHS Class of 2011’s Will Hurley of Stow, who died in a car accident two years ago. With a nod to Will’s years as a star quarterback with Nashoba Chieftains Football, Hurley’s parents started the nonprofit Foundation as a way to assist young athletes in sports training, and to help these students make healthy choices in supporting their athletic goals.

Pointing to the students in the NRHS auditorium last week, Herren declared, “I remember sitting where you are, listening to this [type of] talk. I said I will never be that guy.” But, as Herren stressed, he already was.

“I remember what it was, walking to this assembly, sitting in the back with my friends and laughing and saying hey, all we do is drink and smoke. That’s where it starts, that’s where it ends,” he recalled.

Herren was also a star basketball player in Fall River, something that he noted made him feel above the level of substance abuse. At 14, Herren said, he already was “drinking in the [friend’s] basement, where parents said you were safe, so long as no one leaves.” Except, it wasn’t true.

“Out of the 15 kids who drank in the basement, seven of us turned to heroin, seven of us turned to a needle. Those parents told us we were safe in the basement,” he reiterated. “Back then, I never heard one friend say, I can’t wait to stick a needle in my arm.

“When I was 14, we lost the senior center on our basketball team to drunk driving,” Herren continued. “We went out to celebrate his life by drinking.”

No Safety Net

Still, Herren made it to Boston College and its basketball team. Herren recollected that it was in his first weeks at BC that his substance abuse took off in another direction. “I walk into my dorm room, and there are two girls sitting there, with lines of cocaine.” Though Herren said he turned down the offer to do a line, the girls urged him on, claiming, “This stuff isn’t going to kill you.” Herren complied—and it bit.

After being sidelined by a broken wrist—and failing three drug tests—Herren left BC before his 1994-95 freshman year was out. He then transferred to Fresno State in California and joined its basketball team. Meanwhile, Herren’s chemical habit escalated into prescription drugs. As he described it, “At 22, I was paying $20 a day for a 40 mg Oxycontin pill. I had no idea it would turn into a 1,600 mg-a-day habit, at $25,000 a month, and with a wife and two beautiful kids.” But, the signs were there.

At Fresno, failed drug tests yet again caught up to Herren, who finally checked into a 28-day rehab stay. But, the drug use continued beyond graduation and into a spot on the Denver Nuggets, then the Boston Celtics. It was with the Celtics where, Herren said, his OxyContin was the only path to functioning through a game, even to the point where he waited outside the now-TD Garden for the dealer to show up pregame, and with literally minutes to spare.

After leaving the Celtics, Herren spent several years traveling with overseas basketball teams—and he had dealers lined up wherever he went, he said. His eventual return to the U.S. also brought with it escalating use of crystal meth, along with three drug-related felonies. During one of these, a car crash in Fall River, Herren said he was told he “died for 30 seconds.”

Next came more rehab stays. Herren said the stay that stuck was the one where a counselor advised him to stop putting his family through hell—suggesting he call his wife and ask her to tell their children he had died in a car accident. Herren said he never made that call, “But I went back to my room and started praying.”

Herren is telling his story these days through The Herren Project, and in turn shared reactions of other students with his Nashoba audience. But Nashoba students had words of their own. One student stood up and told Herren, “I’m a recovering addict. I just wanted to say thank you.”

Another moment brought a sobering wake-up call, when Herren pointed to a few audience members that were laughing among themselves. “There’s nothing funny about this,” he admonished. Referring to past losses of Nashoba students and former students to drugs and alcohol, Herren said, “Yet some of you still act up and are still popping pills.”

Herren’s message was not lost on Will Hurley’s mom, Vanessa. She cautioned the parents who may let their teenagers and friends “drink in the basement” that they may not know the packages of problems—such as addictions— that some of these drinkers may be carrying. She added, “And you don’t know what these parents know, and what they may be going through.”