Footprints of History

Rufus Hosmer (1778-1839)

By Stephanie Lewis

On the day that General Lafayette came to town in 1824, the marshal of the day was Squire Rufus Hosmer, a Stow lawyer originally from Concord. Hosmer lived in a grand white house on the Lower Common, across from the Gardner Inn, where Lafayette was received for the celebration of his visit.

Hosmer’s house was different from most others of the day. In fact, it was referred to in many circles as “Hosmer’s Folly.” While most homes in Stow were typical farmhouses, Hosmer’s is described by Childs in her History of Stow as being “unique.” Childs writes, “It has the look of a central part of an English manor house. A square bay in the center of the façade extends up to the second story to the pediment. Inside, you’ll find an entry of a dove painted on the ceiling (some believe this was put there in Lafayette’s honor, which could be so) and no central hall, but two doors, each going into a large living room or parlor. The room towards the west has a scenic wallpaper with scenes from the bay of Naples; it was imported from London at the cost of $450 — a very large amount in those days.”

Hosmer’s house is still standing on the Lower Common, by the Stow Shopping Center.

Beyond being the grand marshal for the visit by General Lafayette in 1824, Hon. Rufus Hosmer was a well-known and well-respected lawyer in Stow and the surrounding area. Hosmer was born on March 18, 1778, to Hon. Capt. Joseph and Lucy (Barnes) Hosmer in Concord. He attended Harvard College and graduated from there in 1800. He married Amelia Paine in 1804, and together they raised four children: Louisa, Rufus, Josephine, and Caroline.

Rufus Hosmer is known for more than being a great lawyer, however. Hosmer was solely responsible for reinstalling the headstone of a former slave buried in Concord’s Hill Burial Ground. The story of how this came to be was told by George Tolman for the Concord Antiquarian Society in 1902. It was published as “John Jack, the Slave, and Daniel Bliss, the Tory: The Story of Two Men of Concord Who Lived Before the Revolution.”

John Jack, a man who began life as a slave in Concord but who was eventually freed, also known as Jack Barron, lived and worked and owned land in Concord. Upon his death, he was buried in the Hill Burial Ground. Unlike other perpetual residents of this cemetery, Jack was not permitted to be buried near others.

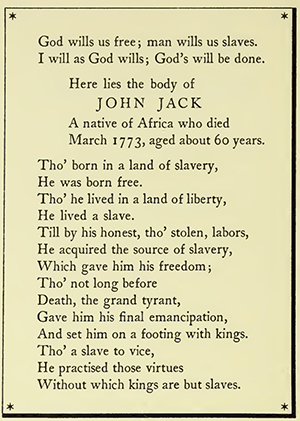

Unlike his perpetual neighbors, however, Jack’s grave contained an epitaph that became famous. Daniel Bliss, a prominent lawyer in Concord who served as the executor of Jack’s will, had inscribed on Jack’s headstone an epitaph that was later copied time and again, according to Tolman.

The headstone for John Jack did not survive the test of time, unfortunately. And by 1830, it was no longer. It was Rufus Hosmer who encouraged others to contribute funds to replace the headstone and restore it to its rightful place above Jack’s grave.

One may then ask what the link was between Jack, Bliss, and Hosmer that had the Stow lawyer feeling the need to replace the headstone. It all begins with the fact that Daniel Bliss was a strong loyalist during the period leading up to the Revolutionary War. He lived on today’s Walden Street, not far from Concord Common. He was often feeding information to the British officials, as he lived close to so much of the action of the minutemen and rebels. At the same time, one of the fiercest members of the revolution was Joseph Hosmer, Rufus’s father. Joseph Hosmer and Daniel Bliss were both neighbors and friends, while at the same time polar opposites when it came to their views on the separation of the colonies from the British government.

Tolman writes, “Can we not imagine that Joseph Hosmer’s son, more than fifty years afterwards, was moved by some chivalric impulse to preserve the only relic that remained here of his father’s old friend and enemy — the inscription that prophesied liberty even to the humblest, in the name of God?”